Tante Hanna’s Memories

Memories: from Moschin to Boll

(1997-1998)

( The Flight 1989)

Johanna Hoffmann

(9/2/1910 – 11/21/2000)

Memories

from Moschin to Boll

(1997-1998)

Moschin [Mosina] p. 1 (English)

(pages)

Grünberg [Zielona Góra] p. 31 (21)

[Grünberg] p. 49 (32)

Seppau (by Grogan) p. 62 (39)

Marriage p. 96 (58)

Wolfsdorf (by Goldberg) p. 99 (60)

The Flight I in 1945

(in the Stenography Notebook) p. 123 (73)

Haldensleben p. 1-19 (appendix)

Süplingen and Flight II 1956 p. 123 (88)

Schlierbach / Langstadt p. 135 (94)

Westerburg p. 135 (105)

Boll p. 171 (114)

Ulrich Hoffmann’s Letter 7th Feb 2005 to Hanna and Tirzah (129)

On receiving the announcement of Gertrude Behrens Krey’s death.

A translator’s Note by Peter D.S. Krey (130)

Ulrich Reinhold Kurt Hoffmann (8/3/1938-4/30/2024), family notes

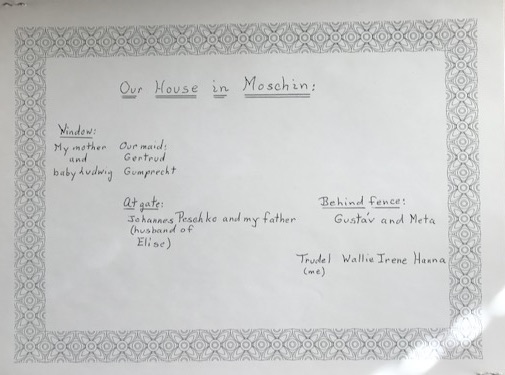

Memories of Moschin

My father was the first to build a house in the settlement of Moschin, which is 4 stations after Posen. It was intended to be a place for when he grew old and a dwelling for his family.

Tante (Aunt) Trudel had already been born on March 1st 1908 and on the moving day, the 23rd of March 1909, while still in Posen, Tante Wally came into the world, so that my mother could not immediately move into the new house.

In front of the house there was a small flower garden, in which my mother, when we celebrated Easter, hid eggs; then in the living room, as well; and even in my father’s briefcase, where we would find some. On the other side [of the front] of the house was the entrance and a long yard that was paved by bricks stretched along before [the house]. In that yard there was a pretty green pump with a long handle. On the right side of the yard began the garden, which stretched out at quite a length and it was bordered with a half-high fence. Behind the house there was the chicken yard with a stall in which there was a pig. When it was butchered, we children often watched it from the window of our bedroom. It was terrible when it squealed that way.

Opposite the chicken yard in the garden there was a beautiful large green arbor. It had a bench on three sides and a firm table in the middle. Its windows had wooden slats on two sides. In front of the arbor, on the side, there stood a great apple tree with little red Christmas apples. From the yard and then along the chicken yard and past the arbor there was a wide path into the lower garden. Right at the entrance on the left stood a large doghouse, in which Ajax slept. When Uncle Ludwig and I were still small, he pulled us around in our little garden cart. Evenings my father liked to stand at the fence and gaze over the fields, and neighbors would come by with whom my father had conversations. Then Ajax would always accompany him, and placing his two front paws on the fence, he was as tall as my father.

The settlement was quickly built up with three rows of houses with six houses in each [row], all having large gardens. It was easy to feel really good there. My father wanted to continue building later, because there were only two rooms and smaller rooms upstairs.

First of all I remember my mother telling me, that when I sat in the baby stroller, Tante Wally let earth worms crawl on my naked back and I screamed terribly. Tante Wally was one and a half years older [than me]. She often sat in the kitchen at the coal box and licked the stone coals. The doctor thought that she perhaps lacked mineral nutrients.

Our toilet was in the chicken yard, which had a higher fence. One time when I had to go, my mother said, “Wally can sit you on it.” We ran to it and when I sat on top of it, she gave me a shove, and my body fell through the big hole. Under it was the huge cesspool. Wally was just able to hold me tight by my feet and screamed. My mother came running and just saved me. I only went back to our toilet when I could sit on it by myself. So I always ran over to the neighbor, who was a carpenter and who in his outhouse had also built a children’s toilet.

Opposite our row of houses there were fields and way behind them there was a brick factory. From there a track ran along the edge of the field to the [factory] works. Our property was on the corner, so on both sides of it, we had wide streets and large fields. On the track [to the factory] there often stood open lorries. We children always sat down on them and one child would push us.

At the beginning of the war, soldiers were quartered in one of the houses. They were having fun themselves pushing us. All of a sudden Wally screamed, “Hanna, get off! There are stones lying on the track.” She had already jumped off. A little boy and I were the only ones still up on it. When I jumped off, the lorry tipped over onto my right thigh. I got a long bloody wound and I still have the scar today. All the kids screamed, “Hanna is dead!” On his two arms a soldier carried me to my mother, who had also already come running. The doctor came and I had to stay in bed a long time; I was probably four years old. Wally said she saw how a soldier had laid stones on the track.

We had our help, Gertrude, until she was married; she wedded a widower, who had little children. We were also invited to her wedding. It was a rainy day and we were wearing pretty white clothes. My mother said, “When we drive to church, be sure to stay in the house, so that you do not get dirty.” As the carriages came back again, I was curious, stepped down outside a few stairs and slipped and fell down. Form the top to the bottom, my beautiful little dress got dirty. Now my mother had to go home with me to change my clothes. The same thing happened to me in Grünberg at Tante Trudel, (mother’s sister’s) wedding, when I was eleven years old. At the nursey, we bought beautiful flowerpots for the altar, went into the church, passed the sacristy, and one step was still left to go in the church. My mother said, “Hanna, watch out so that you don’t fall!” and right, I stumbled and lay half-way in and out of the church and the beautiful flowerpot broken in two. It was somehow pressed back together and still placed at the back of the altar.

I surely stumbled many times in Moschin; perhaps, because I was so small. When on the first day of school, I went to the school with Wally and Trudel, I was five and a half years old and we had to go past the school yard, which was fenced in. all at once an older girl came running out and carried me on her shoulders. Even at recess she often carried me around that way.

In the Schoolhouse we had two classrooms and also only two women teachers. The school was also the same house for the mayor’s office, in which my father worked every day. Through the whole war he worked voluntarily as mayor, because he, of course, received a pension at 74 years of age. On the 2nd of September, the day of [the Battle of] Sedan, it was always festively celebrated – (my father had participated in the battle). In a hall a speech was delivered, my sister Trudel and other girls recited poems. I was also lifted onto the stage and sang the verse of a song which was then sung by the choir. As a baptism sponsor I had a teacher Miss Stelzer from Posen; she was disabled. In the summer she often visited us and liked to sit in our large garden. In it were 80 fruit trees, red and yellow currant bushes but only one gooseberry shrub, because my father thought, only those berries had mildew. We noticed that at our neighbor’s, where we always helped the children scrape the mildew off the berries.

My mother had often invited the teachers [to our house] and from us they received a lot of fruit. Once she wanted to give them glorious egg-plums, but the tree was empty. Wally had climbed the tree beforehand, picked the plums, and had already shared them. She often climbed trees and came down with torn clothes. One day with my father we were picking apples and it was already starting to get dark. Then our old tailor, Miss Weber came into the garden and screamed, “Ouch!” She said, “The apples are already falling down.” Meanwhile Wally had thrown one down on her head.

One day in a black dress, Miss Weber, who was somewhat hard of hearing, came to my mother, who was cooking in the kitchen, and crying, gave my mother her condolence. “Little Wally just told me that your husband had died.” Mother was speechless.

Wally herself often liked to go and see dead people, who were lying in-state in a house. One time I had to go with her and see an old grandmother, but I never went along with her again. One time she lifted a little dead girl out of the casket, when she was alone in the viewing room. When she heard the woman coming in, she quickly put her back into the casket and went out. Because the woman noticed that it was not lying in the casket right, she went to my mother and complained. Wally also often went to funerals. The cemetery of the church was behind the settlement at the edge of the woods. When all the grieving people had left, she distributed the floral wreaths to other graves, which no longer had any blossoms.

For her, homework from school was taboo. My mother first sent her to the folk school and then with me she started in the higher girls’ school (Töchterschule), but she always stayed back. Before I was old enough to go to school, we often went to a land pit. There she and I would slide down the side into the pool of water and come home with dirty underwear, after which my mother would give us a spank on our bottom.

Before that Wally had already hit me, because I preferred to play in the arbor with Liesel Achmann.[1] With the ribbon in her hair, she once tore an earring out of my ear and then my mother had to take the one out of my other ear. I had received the earrings as a present at my baptism.

One time all four of us came home very late in a thunderstorm. We had gone swimming. A red stool already stood in the corridor with a stick on it. First Trudel had to bend down and lift up her dress and got some whacks on her bottom; then it was Wally’s turn; I only received two whacks and Ludwig only got one. I can remember that the stool stood there two times. One time after bathing an undershirt was gone. Trudel said, “Hanna, your shirt is gone.” In the evening, when my mother helped us get undressed, she saw that Trudel had my shirt on.

When I think about how much work my mother had, to feed the chickens, the ducks, the geese and pig; wash the clothes on the wooden wash board, haul the water from the pump, ironing, cooking, cleaning and straightening out the house, also helping with the vegetable garden; so it is no wonder that she reached for the stick, when we didn’t obey. My father did not hit us. In Grünberg I once received a valuable coin (Kopfstück). He went to the barber and I drove our cart to fetch little pieces of wood. He said that I should get off the sidewalk and down on the street, which had cobblestones[2] and so I drove faster and at home I got money for it. (Kopfstücke)[3] Later we girls went shopping in the city.

[In the garden] we also had many beds of asparagus. In the Autumn we often played hide and seek in them. To Trudel Mother had explained how to cut asparagus. So Trudel had to cut asparagus early in the morning before going to school. She often found that there were stems without heads. My parents wondered what animal could have done it. One morning my father said to my mother, “Now I can tell you who the rabbit is!” He saw how Wally crawled around through the beds and bit the heads off; they also tasted good when raw.

Once my mother took Wally to Posen to go to the dentist. Before it she had been crying for days because of a toothache. At the dentist she would not allow the dentist to pull her tooth; as the dentist became more energetic, she bit his finger. For days he could not work. But Wally cried even more at home. So my mother said to me, “Hanna, show me your teeth; that one is also no good anymore. So you can come along to Posen and let your tooth be pulled. Wally will watch, then she will surely allow her tooth to be pulled as well.” At the dentist I, of course, allowed my tooth to be pulled and then Wally did too. Mother bought us both tall laced shoes, mine black; Wally really wanted brown ones. Summers we of course went barefoot. Then I had to get a tooth pulled again because a new one was coming. My father went to the barber and said, “Come along and let him extract it.” The barber pulled my tooth and I went home.

When still a baby Ludwig became very sick and the old doctor came again and again to see him. As he lay dying, my mother took him out of his little bed and put him on her lap and breathed her breath into him for hours. The doctor who came back, shook his head and said, “Why don’t you let him die?” My mother did not listen to him. So he went to my father in the garden, saying, “She should let him die.” My father said, “Nothing I can do.” Later when the doctor entered the house again, he saw that Ludwig was lying in bed asleep. When he later saw him in the street, he said to him, “I did not bring you back to health; it was your mother.”

After Abendbrot (the evening meal) he often came to visit my father and also said “Good night” to us children. He liked to hear our songs and prayers. One time he even took me on his lap and let me hop up and down. My mother said, “Watch out! Hanna did not eat Abendbrot that long ago.” And she was right. He soon had my Abendbrot all over his shirt and suit.

Trudel told my mother, “A pupil stabbed himself in the finger with an ink pen and now he’s gotten blood poisoning. They want to amputate his hand, so I counseled him to come to you.” He came and my mother bathed his hand daily for a long time in soap water, and then put a salve on it, that my father swore by. The boy’s hand healed and his parents felt very thankful to my mother. We also had a black pill that we children had to swallow, when we had a cold. I could not make it go down, so I always had to take in tea. In the evening we also had go in bed with my father and sweat for an hour. Oh, when doing that I always cried.

On the back of my right hand I suddenly got a great many warts. “I promise to rid you of them” (die versprech ich Dir), said my father. He took me to the front door of the house and [in the light] of the waxing moon, I had to look at the moon with him, “What I am seeing grows and what I feel diminishes.” Meanwhile he stroked my warts with his hand, saying “In the name of God, etc.” In a few days my warts were gone. In that way he healed (versprochen) several sicknesses, even a woman with facial shingles (Gesichtsrose), after which he always had to lay down.

My mother wanted to change the bed sheets, so she went upstairs, to the bottom drawer of the dresser, where she had the laundry. As she bent down and pulled hard to open the drawer, she found herself sitting with her posterior on the floor; the drawer was empty. The door of our house was never locked, so a gypsy woman must have stealthily climbed up the stairs and stolen the laundry. From the neighbor she had even stolen the cooked laundry that was cooling and stood in a bucket at their front door. Gypsies often hung around and were always chased away. We put a birch broom in front of our house door thereafter so that they would not harm our animals.

When I was seven years old I went to piano lessons with Wally. Trudel, for one year, had already been with Miss Stobbe, who with her aunt, – the uncle, the head forester, had shot himself – lived close to the railway station. For us it was a long way through the whole city and over a wooden bridge. At our home in our living room, – we called it our good living room,[4] we had a big grand piano. Wally and I practiced every afternoon and I was proud when Miss Stobbe gave me the grade: very good. Wally always played more quickly and so one time she raced in a congregational celebration down through the [song] “Sled Ride” in descant (the high notes) and I had to play bass, and that, even though I had smaller hands. Out loud I said, “Don’t play so fast!” and everybody laughed.

On top of our grand piano, in back, was a bottle to which my mother went daily and took a swallow. We were curious and also took drinks from it. In order for mother not to notice anything, someone always had to be playing the piano. My mother wondered how the contents of the bottle could always diminish so fast. So once she surprised us during practice, while I was just taking a swallow. Then the bottle disappeared. My mother had cardiac asthma and my father always bought her good cognac; he said, “That will make you healthy!”

We only went into our special living room when visitors came or on holidays, otherwise we always hung out only in our big kitchen.[5] Next to it was the large bedroom in which there were four beds and one children’s bed and right on the left, when one entered, there was a beautiful red cockled stove. We often sat on the bench of the stove in the evenings while my mother read stories to us. In bad weather we wrote with white chalk on the bedroom walls, which my mother permitted.

Irene’s father, whom we called Uncle Gustav, came to us every Sunday during the war and with a full pack he drove back to Posen again in the evening. He had fruit, vegetables, eggs, sausages, chicken meat, bacon and pork. Our pig would mostly weigh 500 lbs. before it would be slaughtered.

One night my father heard the pig squealing and rushing out, he was just in time to chase the thief away. We did not have our [dog] Ajax anymore. He had gotten too weak, because at the end, he just lay chained all day.

Tante Meta and Irene visited us for longer periods of time in the summer. Once we took them along to pick blueberries; the forest was just behind the settlement. Irene picked a cup full for me and then she laid down in the grass. Together we had picked a whole bucket full, which my mother put together with Ludwig in the children’s wagon. Really pleased and with blue hands we went home again. In the forest it was always joyful, we looked and called for one another, and the butter bread and water tasted glorious. It was bad when the little pot sometimes tipped over.

All the siblings of my mother came to visit us, as well as grandmother. She was my baptism sponsor. Tante Trudel and Tante Meta were Wally’s. Tante Liesel, for Trudel and Uncle Erich, for Ludwig.[6] Grandfather was, of course, angry with my mother, because she left him in Grünberg and looked for work in Posen. She became a help in an officer’s family. Only when my father drove to the grandparents and asked for [my mother’s] hand in marriage, did they become reconciled again. The brother of [our] grandmother was a physician in Marienwerder; he and his wife liked my mother. They wanted her to come to Marienwerder and become a sales woman and work in the Wagner’s cleaning business. My grandfather did not let her go, because at home she had to do everything. Then Tante Liesel asked my mother if she could go [in her place] and there she married uncle Herrmann.

My father with uncle Gustav worked for customs in Posen and before that my father was a soldier for twenty years, finally a sergeant and master swimmer. When his first wife died, he spent some time living with his daughter, Elise Peschko (her husband was Johannes Peschko, who was killed in action as a soldier in the war). There [my father] became as poor as a church mouse along with their many children: Gottfried, Hilde, Gertrud, Toni, Ruth, and Bernhard. So he moved to Posen and looked for a place to live. On Wednesdays with uncle Gustav he went to Tante Meta to eat. They first had to peel potatoes when they came, so he soon stopped going there and looked for a place to eat the midday meal.[7] In the Lutheran church he got to know my mother, whom he married in October 1906.

In Posen they had a beautiful allotment garden (Schrebergarten).

After the war my father was still supposed to remain in Moschin as the mayor, but my father said, “I don’t know Polish and I don’t rightly trust the translator.” In 1920 he received the information from the German government that he would no longer receive his pension, because he had always gotten paid only in Polish currency.

Also the Congress Poles had now arrived and [fearful of them] many Germans had taken flight, especially the Jews, who had stores all around the market place.

The Poles took my father out of the front door of the house and wanted to shoot him, but the Polish inhabitants came on the scene and screamed, “He only helped us! He should not be shot.” So at that, we could wipe away our tears. When the neighborhood learned that we were going to leave Moschin, some came and wanted to buy the property; a farmer’s wife even brought 30,000 DM in gold. My father said, “I can’t take money like that, because I won’t be able to take it over the border.”

My mother said, “Take it already; I’ll hide it!”

“We will be searched to our skins, we can’t take it.” He said. So a Pole came out of Posen and said, “I’ll pay you 2,000 DM in Polish money and to Germany, I’ll send to you 43,000 DM in German money, which should arrive in Germany already today.” That my father believed him, even till today, I shake my head in disbelief.

The teachers had already left and crossed the border a half a year earlier and there was no school. A Polish teacher came later and I still only know, that with Wally, I sat in the school in the afternoon and I was supposed to read Polish. The school had really closed. All the children had left for Germany with their parents. The Polish children went to the Folk school.

My mother packed a travel basket; the official watching took some things out again.[8] The furniture was loaded up and many [pieces] arrived broken in Grünberg. We had to leave the grand piano there. On my birthday, the 2nd of September, 1920, we went to the train station and made it to Bentschen, where we spent the night in the hall of the railroad station. We children sat on a bench and laid our heads on a table in order to sleep. I could not sleep and watched as my mother rummaged through the travel basket. She probably had still hidden something that she saved. I was restless and she said, “Why don’t you sleep?” The hall was filled with people.

The next day we women had to go into a room, where we had to undress to our skin. Everyone was allowed one piece of jewelry. So I had a chain from Miss Stobbe. (She had come over to us and said that she had no relatives in Germany, and asked if she could also come to Grünberg with her aunt and then asked if each [of us] would take a piece of jewelry along, because she had so much jewelry.)

On the other side there was a room in which the men were checked [by officials]. My siblings dawdled around and I went with my mother to the officials’ table, where the basket was searched thoroughly. I looked at the official with big eyes and he asked, “Why are you looking at me like that?” So he only looked at the top of the basket, saw a whole loaf of bread, still lifted something up and said, “You can close it.” My mother was relieved and looked at me full of love. Then we traveled to our grandparents in Grünberg.

There is more [in Moschin] that I forgot. In the Spring my father had picked worms off the cherry tree and one kid stood under him and each of us had to take turns at the ladder and put the worms into the tin can. [When it was my turn] I was always unhappy; I could not be expected to touch a worm. So he had to throw them into the can. Oh, my, when they missed the can, it was thunder and lightning up there.[9]

On Sunday afternoons we went with him to the potato fields and pulled out saltbush and put it into a sack for the pig and we gathered chestnuts as well, which I liked doing. When he came home from Posen, we always ran to meet him and searched his packages and pockets, because he always had sweets for us. He also bought clothes for us which he bought from the Jew, Petersdorf. In those clothes we were once photographed by a soldier in the garden.

One time my father was taking the manure out of the pig stall and let the pig run around before it.[10] He stood with his legs wide apart in the door of the stall and the pig ran through his legs, riding him out of his stall into the chicken yard.

On vacations Trudel and I went to a farm of a woman who had been a neighbor of ours in the settlement. Besides small farm animals, she had three cows and among them a wild one and beyond that a servant. When I awoke one morning, she had gone to the city with Trudel, probably to sell butter. Now I had to herd the cows. The young wild cow naturally ran away from me and the servant had to capture it again, so I did not want to stay there any longer. We were so homesick anyway that we always went to the outhouse[11] and cried our hearts out. We still stayed there 14 more days.

One time my mother went with us to the circus in Posen. I myself remember how a dolphin with a petroleum lamp on its nose, as large as our lamp, wiggled itself up onto a podium and then slid back down on the other side. I was speechless. Uncle Gustav often brought us petroleum, because where we were you could not get it anymore. Later we used carbide which smelled horrible.

My parents needed passport pictures, so they let themselves be photographed by the house in front of the espalier pear tree, from which we harvested giant, juicy pears. In the picture my father looks wretched, but in contrast, in Grünberg, five years later, he looked much better.

Once in a while in the evening we were allowed to beat one egg in a cup. The egg white had not yet become stiff, when we already had eaten it. Only Wally did not get finished. When my mother went to her, she had beaten the bottom out of the cup and the fluid of the egg was all over her apron.

At Christmas Tante Meta always sent us a package and often there were meringues in them that tasted especially good. One time a real large one arrived, which my mother immediately carried into the special living room. We were naturally curious. When my mother was in the chicken yard, we girls snuck into the room and crawled under the table and under the sofa we found three beautiful dolls. Each of us said, “That one is mine!” and then we really received them on the gift table for presents.

We always celebrated Christmas beautifully. The forester always brought us an especially tall tree, which was placed into the red stool, which had a hole in the middle. The tree [was so large] it almost reached the ceiling. My mother always trimmed and decorated it and we were not allowed to see it beforehand. On Christmas Eve we children sat in the kitchen and waited for the ringing [of a bell]. When the door opened the shining lights of the many candles and the colored ornaments of the tree came over us, and nuts, apples and sweets also hung on it. My mother sat in her wicker chair with my father next to her, and then we first sang a song, after which we gave our parents our Christmas folders. In its pages we had written the poem and upon its first page, we had drawn something for Christmas. Each of us then recited their poem and then we sang again. We also played piano, and then we were at last allowed to go to our places. I no longer remember all the things I received, but I loved books with fairy tales. Then we were allowed to nosh [on sweets] and play; then last of all, we still had poppy seed dumplings.

During the war in the winter, the call came for all of us to flee. My mother had already packed the travel basket and we all stood around thickly dressed, when suddenly the news came that Hindenburg had won the Battle of Tannenberg.[12] All of us then could breathe a sigh of relief.

One night the brick factory was burning. My mother, who washed her feet late at night, heard screams, opened the kitchen door, and saw the factory burning through the hall window. She immediately called my father, who quickly got dressed and ran with the settlers to help put out the fire. We children also had to get up, because my mother was afraid that sparks could fly over to our house. So we went to see the fire. The owner ran around in the field like he was going crazy and the cook, who had been in her deepest sleep was so agitated that she couldn’t do anything, only her daughter helped with quenching the fire. After that there was no longer any work to be had there.

Memories from Grünberg

My grandparents lived in Grünberg, Lanwitzer St. 8. There they, [the Déus’s] had a small house, a large garden and many adjoining buildings. Before them, the grandparents Kleint lived there with my mother. The [Kleints] had only one daughter Christiane, who married my grandfather Déus and with him, gave birth to seven children. Grandfather was the business inspector for the district of Striese in Trebnitz. His wife died at 34 years of age, the first mother of my mother, and took her youngest son, who was one year old, with her into the grave; both had consumption.

The children Oscar, Gustav, Valeska, Gertrud, Liesel and Alfred received a stepmother, Magdalena Gessner, daughter of the [Church] Superintendent Gessner: she was an evil stepmother. A son Erich also still came into the world.

For a short while we lived with our grandparents, all of us sleeping on the floor in the large room. After a short time we received a kitchen and a room on Green Street. Then my parents loaned money from the city and bought a little house in Neustadt Street. There we also had only a kitchen and a small room. It was a long house. On the other side of it there lived a worker-family, with four adult girls, who all went to the factory, and they had a boy. They often stole things from us. Above them was an attic and over us, there was a small room, in which an older worker lived, who always came home drunk. After five years he finally moved away.

Trudel and I went to the Lyceum, but demoted by one grade, because for a long time we had not gone to school. My class-mates were the same age as me, because I had already started in school when I was five and a half years old. I had one pair of high Polish shoes, so in the summer I went to school barefoot. My mother said, “You certainly will not be allowed in[to the school] that way!” But I went. All the women teachers stared, but said nothing. Director Hartmann was also a refuge from Posen, so he knew what we were going through. The next day, half of my class came in barefoot, as well as the pupils, the girls from the lower grades; they, then came in barefoot, too. But on the sidewalk one always had to walk fast. [Probably because the pavement was hot.] Later I received shoes from the refugee association.

I had many girl friends: Henny Starke, Gisella Becker, Marianne Hirthe, Marianne Baum, Ursel Lange; they always invited me to their birthday [parties]. They also came to mine; my mother always baked beautiful crumcakes (Streuselkuchen). Afterwards we always played in the side street, which was very wide.

G. Becker, the daughter of a veterinarian, always sat beside me in school. In recess, for a long while, we would bring me a sausage sandwich and she took my sandwich with margarine. In our class we got along well together. At recess we all played dodge ball. One team[13] had Lotte Vitensa and I had the other. I was very good in gymnastics. One morning Miss Boehm wanted to know when our fathers were born. When I said 1841, the whole class howled, but Miss Boehm quieted them down quickly.

Miss Stobbe with her aunt had found a residence right opposite the church. Because we had no piano, only Wally was allowed to play at her place. She often visited us with her aunt. One Advent Sunday the refugee association had a Christmas celebration. She practiced a piece from the theater with me, in which I played her daughter and I had the leading role. I played the role in a wholly natural way. I was not at all afraid, so I got lots of applause.

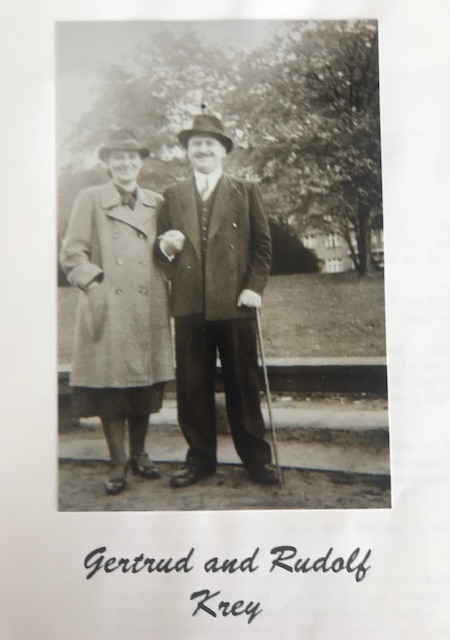

Every once in a while the school physician came to school. Examining Trudel and me, he discovered that we had enlarged thyroid glands. We had had them a long time and we always smeared iodine on them. The physician gave the counsel for us to have an operation. Trudel was fourteen and a half and I was twelve. The first night after the operation was terrible. I tortured the night-nurse constantly to give me something to drink, but she was not allowed to. Trudel had a cold and coughed continually and because of that she kept a thick scar. The Helping-Preacher Rudolf Krey (Hilfsprediger) came to visit her daily, and, of course, a half a year later they were engaged.

One time my mother brought five girls, who all came along to visit me [in the hospital]. Marianne Baum could not take ether and she fell over [i.e., fainted]. In the beginning, when I went home, I did not do well. My German teacher, Miss Böhm, the daughter of Pastor Böhm, visited me and brought along butter and eggs. Now she also saw how little space we had. In the religion-hour everyone prayed for me. I found that out later from Hilde Meinhardt.

Tante Trudel married the stout (der dicke) Henry, who was employed at Beuchelt; Tante Liesel, Uncle Hermann, Tante Lina and Uncle Erich came to the wedding. Uncle Oscar had taken his own life. He was an employee at a bank and had often loaned money to Uncle Gustav, who was a soldier, and who could never repay him. When the bank noticed it, Uncle Oscar had made a quick exit(Kurzschluss gemacht).[14] In World War I, Uncle Gustav had lost a leg, divorced his first wife, with whom he had a son, and married a capable woman, who in Breslau had a milk store in the hall of the market. Evenings she often had to look for Uncle Gustav in a bar.

Our family was also invited to Tante Trudel’s wedding. Just as well, my mother had to pre-cook and pre-bake everything for it anyway. Tante Trudel had a miscarriage, so they went and got Horst out of an orphanage. The mother, a tailor’s daughter from Berlin, was not allowed to keep Horst. After the war, he married a woman from Holland and became a physician. Later Tante Trudel also adopted Hans, with whom she fled to Uncle Erich. Later Hans married and lives in the G.D.R. Horst did not concern himself about him. He received Uncle Erich’s inheritance, the house and property, which uncle Erich had received from his grandparents and then [Erich] bought a practice in Cologne. Naturally, Tante Trudel was behind it.

Years earlier, Grandfather had divided the land behind the garden among the other children. For very little money, fat Henry (der dicke Heinrich) begged my mother out of her land. Later the city bought it and developed it and he received far more for it. But that money did not bring him any luck. Beuchelt had fired him so he wandered off to Australia in order to make big money there. Afterward, when Tante Trudel continually had to send him money, he came back with sacks full of furs, which already stank. They lived in Bergel, in a small house, which stood off and somewhat higher in the yard of their grandparents.

One day Tante Marie with Trudel and Lene[15] came to us. Uncle Alfred had died. They had no money and Grandfather did not like them. Uncle Alfred with his family had also fled from the region of Posen. There he was the rent collector (Rentemeister) for a estate(Gut) and things went well for him, as Trudel in Überlingen told me. So they went to Sorau and Uncle Alfred found work in an office. Hans was a gardener and he drowned in the Oder [River] in the beginning of the 30’s. Gerhard also learned to be a gardener. Both little ones, Marianne and Alfred were in the orphanage in Freystadt.

For a while the three stayed with us. We four girls slept in one bed and each one of us yelled when the legs of another struck her in the face. Thank God, my mother soon found them a room and a kitchen, where they could all live together again. Trude and Lene earned money as house maids and Hans probably also helped. Trude married Harry Pohl and had Orla, who also had a daughter, who is still studying. Alfred married Lotte and they had Heidrun, who has two children. Gerhard had a garden-nursery in Frankfurt, On the Oder, but never returned to it after the war. His wife did not come to the West, so he married Alfred’s wife, who was a widow, because Alfred [a soldier] was killed during the war. Gerhard’s son often comes to his Tante Trudel. Marianne, who is also dead, has a daughter who lives in Ludwigsburg. The siblings of Trudel have all died.

Wally entered the Folk school [going to the class] according to her age, which was the second; the class, she was supposed to attend for two years in order to attend the first class for two years. But she stayed all four years in the second class. She did not understand, “What that old teacher taught,” so she took little dolls along to school and played with them under a tree. Her neighbor, Gertrud, who lived behind the cemetery, had to do her homework there in the cemetery for her; and woe to her, if she didn’t do it. In the evenings my mother practiced the poem [she was to recite] with her and meanwhile I was supposed to be able to do my homework. The only good thing: I could at least do all my writing homework on my father’s desk. In the test [given] before her Confirmation, for her turn, she only had the first commandment.

After her time at school, she stayed for a year with Uncle Erich, who was the Inspector of an estate (Gut) in Laubsky near Namslau. In the long vacation, I was allowed to visit her. Uncle Erich and Tante Lena were very nice; they had no children. Wally was also with the Peschkos at Rothenburg 10 for a time. The elderly clergy [couple] (Pfarrersleute) had four boys and two girls. Their mother still lives with her youngest son, Philipp, in the parsonage; he plays the organ. He was a little too grownup and once wanted a kiss from Wally, so she painted her lips with thick red lipstick and planted a hefty kiss on his cheek. When his mother saw the mark on his cheek, she was shocked [and angry].

Johannes, her oldest son, had married Father’s daughter Elise and [as a soldier] in 1914 he had fallen in action. Karin Strobel is a daughter of Ruth, who is the youngest daughter of Elise. Adelheid is a daughter of Peschko’s daughter. It was still later that Adelheid married Karin’s Father, Edwin Löwenhaupt. Ruth died of cancer. All the other siblings have also already died. Rosemarie is a daughter of Gertrud. She is the second daughter of Elise, was a nurse, and married a physician.

Before their confirmation, all the confirmands had to go to Freystadt for four weeks of instruction, which took place in the room of the superintendent. When Trudel had to travel there, my mother awoke me in the morning and said, “Hanna, you have not yet finished knitting Trudel’s stocking.” I still had to knit the toe. Neither Trudel or Wally knew how to knit. For Christmas my father, my mother, and the grandparents received wristlets, gloves, and socks. For twelve years already I have been knitting a long, dark red jacket, which I unraveled in Seppau, and from it I am knitting a small [jacket] for skiing. I also knit warm cloaks for my mother and Anna Hoffmann. “That is the first handmade work that I have received,” she said, so in Wolfsdorf I knit her a pajama top (Bettjäckchen).

The gathering of children who came to the confirmation instructions were from Freystadt, Neusalz, Grünberg and the immediate surroundings. Counting me, it was about 20 children. The test took place in Freystadt and I was confirmed in Neusalz, because we were only three confirmands out of Grünberg and with the Neuzälzers we were seven. At home there was only coffee and cake. Grandmother and Tante Trudel came, and Trudel also came back from Hamburg. She had seen off Rudolf, who had departed on a steamship for America. Without money, he was instructed [in the seminary] for America, because his parents – his father was a baker, had no money for his studies. In two years Trudel was to follow him. [Without being a bride] she would have had to wait seven years. So they had a civil marriage in Hamburg.[16] Rudolf needed only a half a year to pass his exam, so he asked my father to send Trudel earlier. She received mail from him on a daily basis.

A huge send-off for her took place at the railroad station with relatives, friends, and acquaintances and tears; only I had none. I was carrying a pot with plum pudding for Grandmother Krey, which I only gave her, when she was already in the train, and thought, “You will of course come right back.” In 14 days she was on a steamship for America.

The summer after I finished with school I traveled with Grandmother Déus to Marienwerder. Going through the Polish corridor, the [doors] of the trains were locked. Uncle Hermann had a factory for cleaning, dyeing, washing and knitting. More than a hundred workers were employed. I helped Peter and Dieter with their homework [school assignments], dusted in the mornings, and helped Tante Liesel in the kitchen. The maid did everything else. On Saturdays we went to the market with Grandmother Wagner to buy vegetables and meat, which the girls carried home. We three still continued to the confectionery for a cup of coffee and cake.

Tante Liesel had tea parties (Kaffeekränzel) with some ladies and in that way I got to know Ruth Falk and Erika Weyer. With Klaus and Jochen they attended a dancing school and I was always allowed [to go] with them to a little dancing party (Tanzkränzchen), but sat with the parents, but I was also asked to dance. There in Grünberg the superintendent had forbidden attending the dancing school. When a dance party took place without the parents it really frolicked.

Klaus wanted to kiss me on the stairs, so I screamed, “Jochen, help me.” About that he was so angry, that on the next day, he told Tante Liesel that I had not behaved well. Ruth Falk, who learned about it, told Tante Liesel, that everyone was just having fun. From that time on I let Klaus stay on the left; he was the favorite of Tante Liesel. At the office party of the Wagners, he danced a lot with me and commented that we should try to get along again. Later Klaus became an agriculturist and acquired an estate (Gut) in Danzig. He married a teacher from Berlin, from whom he got a girl. He was killed in Berlin as the city was being defended.

Jochen, who had a glass eye, still survived and made it out of Stalingrad. After the war, with his father, he again rebuilt the old cleaning factory. When they started making a profit, the owner took [the factory] back. So they came to Hamburg and arranged a cleaning and laundry business in old abandoned barracks. When they were torn down, Jochen bought a new factory – Uncle Hermann had already died, indebted himself and died of cancer. His marriage was not a happy one, but in spite of that they had three children.

Peter, who became a big and strong boy, would seat himself in an easy chair (Lehnsessel), after every Midday meal (Mittagessen), drink a mug of milk and with it, eat one bar of chocolate; and was a pilot, like he had always dreamt of being one. He was shot down in France and could still jump into the water, but he was still hit by a bullet. The French buried him. One time, Klaus visited his grave.

Dieter married a daughter of a hotel owner from Bavaria. When my mother died in December 1949 in Haldensleben, he had just returned from Russia as a prisoner of war. In the beginning he helped Jochen, but then left for Bavaria with his wife and three children, where he soon died. For Christmas I wanted to leave Marienwerder and go home, but then Grandmother Wagner asked me to stay with her for another half year. Grandfather was a diabetic and had to get one leg amputated. Now he always stayed in bed. Two nurses cared for him. I did many small jobs and sometimes I went shopping with Grandmother or we did handicrafts. She was the third wife and played the gracious lady. Grandfather soon died. He had a big funeral; now we often went to the cemetery.

In the summer, when I wanted to go home, I still travelled to Paulshof to the Weyers. Erika had invited me. Her sister Annemarie had a home[school] teacher; she did not want to go to school in the city. Gottfried directed the factory, which was indebted. I never saw Mr. Weyer outside, but only at his desk. But his wife was diligent. I slept in one room with Annemarie.

I became active right away in that I took the fresh milk on a cart with an old horse on strings, they did not have ropes, and rode to the dairy. One had to ride through a gorge, which I could not find on the first day, so I rode down the long avenue and arrived with sour milk. The good folks only then showed me the way through the gorge. I always got angry when the string broke and before I noticed it, the horse went around in circles. In spite of it, I drove [even] further on a daily basis. One morning I drove Mrs. Weyer to the railway station in Allenstein, and I was supposed to also go shopping in the city. She gave me a list and on it I read one hundred pounds of potatoes, among other things. Was I also supposed to take along 100 pounds of potato flour? The merchant called at the house, but no one knew anything about it, so I took him along. When Mrs. Weyer came home, she said, “I wanted to take along 100 pounds of potatoes for the homemakers’ association;[17] I had forgotten them.

In front of the manor-house (Gutshaus) there was a big lake and we daily swam around in it. In one corner of the lake there were many clinging vines,[18] in which I once caught my foot. I had a hard time disentangling myself. I also helped with the harvest. It was a hot summer.

They were good friends with the owners of the landed estate (Gut) next to them. The wife was dead and the son and the daughter with her husband ran the business. Once in a while they themselves visited.

I often went into the woods with Annemarie to look for cranberries, on the way back we often passed the Schlüters. One evening we saw a white spot in front of us. We were afraid but we continued on bravely, and then we recognized a white horse. In eastern Prussia, I was always awe-struck by the tall trees.

In Marienwerder there was Pastor Schulz, whom Grandmother liked to invite over to eat. He was always very friendly to me. Irene told me that he previously had been in Düsseldorf and had wanted to marry her, but because everyone in the church started whispering, she did not marry him. When Ruth and Priscilla visited Pastor Schulz in Berlin, – he was the baptismal sponsor of Matthias, I was just visiting Rieke, who was studying there. So I still wanted to say goodbye to Ruth and Priscilla and I was astonished, when Pastor Schulz opened the door. He greeted me heartily and showed me photos of Marienwerder, where we both, with the singing club, had been photographed together. He married a daughter of a Peschko son.

Grünberg

My father often went to the Grandparents to help out in the garden. In the long vacation we children had to pick currents and gooseberries. There were long rows of red and yellow berries. The yellow ones were at least sweet. Then in large tubs on a farm cart we took them to the winery, which was nearby, where it was all uphill. Later the plums had their turn, as well as apples and pears, and last of all, the nuts were knocked down, which we had to gather. Doing it made our hands hideously brown.

In the evenings my father read the evening blessing and later I had to read it. Wally, who never listened, always laughed. She sat pretty next to my mother. It was terrible in church, which we attended very Sunday, especially when Uncle Erich came to visit. Her laughter was contagious for him and the whole pew shook; could the Grandparents never have noticed it? In any case, they never said anything. Wally probably always thought about what mischief she could always do again. Once she put an ear worm in Marianne Hirthe ear; she never came over again. She beat up a schoolgirl comrade of Trudel, and [that friend] was speechless, when she learned [Wally] was Trudel’s sister.

On Sundays [Wally] would often go to the cinema and listen to the music, which at home she would practice on the piano. Trudel, who was now already engaged, always quarreled with her. In the cinema a [fellow] engaged to the Hannusches’ girl played the violin, because at the time they were silent films. One time with his violin case under his arm he had to disappear [once] again. He went into the yard, behind the toilet onto the boards over the cesspool and fell in. He just barely saved his violin. He screamed loudly [for help] and everyone ran over and pulled him out. So naturally he had to totally change his clothes and that made him come late to the cinema.

Ludwig played the harmonica wonderfully. In the evenings he would sit down opposite us in the garden and play the most beautiful songs and operettas. Then in all the houses, they opened their windows [to hear him playing]. A wife of a professor once told me, “Since you have lived here, we can once again go through the alley to the Railway Street. Before [you came] we were always spit on.”

One evening my mother said, “I’m just always hearing steps at our window.” She opened the door and she saw an old man standing outside.

“I am always [eavesdropping] on your beautiful evening blessing and listening to your beautiful songs.” he said as he excused himself. My mother could not, however, bring him inside, because my father was now jealous of every man, even of Rudolf, until Trudel told him that he came for her sake.

When for Easter [Rudolf] came back to us for their engagement – he had been again in Hamburg, because our vicars were exchanged each year, he slept at Mr. Reiskidhen. At night there was suddenly a shaking of our house door and an intense knocking at our window and someone screamed, “Your roof truss[19] is on fire!” My mother got up immediately, opened the kitchen door and screamed, “Yes, I smell smoke! Trudel, get up; wake up Rudolf. Get him to put out the fire!” Rudolf investigated the attic thoroughly and said, “Nothing is burning here. The chimney is completely cold.” When my mother went outside, the Hannusches were also outside and more people were also out in the street. Then we read in the newspapers, that two young men also tricked[20] the Catholic Parson and the midwife in the retreat center Lübtenz, that lay on a hillside (Anhöhe). Both met each other when they were on their way. Half of the city had been tricked by an Easter lark.[21]

Here they also carry out Easter larks, garden doors and ladders are dragged away, and masses of toilet paper are trailed through the streets.

I looked for a job in an office and I found one by representative Fröhn. There I learned to type and [learn] the Latin handwriting, because in the cash account books everything had to be recorded in Latin [handwriting]. In school we wrote only in the German [old Sütterlin] handwriting.

The Fröhns had three sons: Horst, Hans, and Heinz. The two year old came into my office every day, so I laid him on a sofa cushion on the carpet and he went to sleep. Sometimes I looked out of the window with him, too. Mr. Fröhn was out-and-about all day, and in the evenings he would always tell me what I had to do the next day. I was there for seven months. I wanted to learn the double entry book-keeping and stenography. So I served in the print shop of a weekly newspaper, where I could sometimes work mornings, and learned from Teacher Stark double entry book keeping and stenography along with it. Grandfather said, “Also go and learn the agricultural business bookkeeping, you are so anemic that you need country air.” So I drove to Breslau and learned it in fourteen days. Almost all of those taking the course there were sons and daughters of propertied estates.[22] As we ended one class, I said, “We forgot to take one foal out of the record book.”

“That’s right,” said the professor, “that one croaked. One day you will be a good secretary.”

I was friends with Lotte Ehricht. Her father had a bicycle shop in which she helped out. There I got to know Kurt Gerlach. Lotte also had a friend, so on Sundays we took a walk together. Sometimes Kurt also visited us in the evenings, but then he didn’t go home, but went to a bar. From his mother I also learned that he also befriended himself with someone else, whom he later married, but was not faithful to her, as Wally told me, so we separated.

Lotte visited us very often; she had no siblings. On Sundays we often went to a confectionary shop, where there was also dancing. It was always a lot of fun.

In the newspaper I read that in Berlin, Fleisch-Tresto (Meat-Tresto) was searching for an employee as bookkeeper for its agrarian business. I applied for the job and was accepted. The owners had a villa in Zehlendorf and an agricultural estate nearby. In the business association there was a young inspector; he had a little boy and his wife had died. We were three girls, who arrived at the villa and we were greeted by a niece of the owner; she was his secretary. On the next day she drove with us to the office in Wilmersdorf, where several employees sat in four rooms. The three of us had long sheets of paper with numbers placed before us, which we had to add up. In the evenings we slept in the villa, and there we learned that the wife had hanged herself. He was a colossus of a man. On the next day we rode in a streetcar to the office and again had to add numbers together. After three days both other girls had disappeared, and they did not tell me why.

On Sunday I drove to Tante Elise -(we called her Tante). She said, “You really don’t have to stay alone in the villa; come stay with us. We will make ready the guestroom, which had no window, and set up a bed for you in it.” With that, I preferred the villa.

On Saturdays an older employee went with me to the fields of the estate. For a quarter of an hour we walked through garden plots (Schrebergärten). She gave me the accounts for the amounts of the wages of the workers and I had to count out the cash to pay them. That was my whole job on the farmland of their estate. The inspector told me that the woman employee did the bookkeeping. I took a look at the horse barn and the fine riding track and learned everything from the housekeeper of the manor.

The office was in the city and everything proceeded noisily. In the streets you heard the streetcars and automobiles. One of the book keepers complained loudly, because she could not find a mistake [in her figures]. One yard was the yard used for butchering and a little farther away, there was the factory, that made sausages. We received our lunches (Mittagessen) in the office. Many a time I had to go into the yard to pass orders on [to the workers]. All of this did not please me, so I gave my notice. The woman manager was upset and said that the other girls were laid off because they made many mistakes, but I had done everything correctly. She herself also had started with a little job and had become the manager, and I should stay. I wanted to be on the land and not in a city office and so I let her give me my last wages and I drove to Tante Elise, who was not at home.

But Bernhard begged me out of fifty Marks. Tomorrow he had to pay his tuition for school and had no money and he really wanted to continue at school. At the baker’s and the grocery shop everything bought was recorded and had to be paid on the first of the month and again, it was from my money. Onetime Ruth did not get bread, “First pay up your debt!” the wife of the baker said. They kept a washerwoman for help and on that day there was meat for the midday meal, on other days Ruth made cabbage soup for me. Hilde, who worked in a bookstore earned only 90 Marks – ranted and railed that they still lived in such an expensive house, they could move into a smaller one, but Tante Elise needed a salon.

Erwin Löwenhaupt, who was an engineer, rented the little room, so a little money was there again; later he married Ruth.

Wally, who worked in a small guesthouse in Berlin – the guesthouse owners treated her like their daughter – was visited by my mother, who slept in Tante Elise house. She took along a great deal of groceries and wanted to eat the midday meal [at her home with her]. Tante Lise, however, drove into the city with [my mother] to eat and my mother had to pay for everything. On the next day, my mother already left. Tante Elise often went to Wally’s in the evenings and always got supper there (Abendbrot). Her children were, of course, already grown; they had to see how to fend for themselves. They lived in the most beautiful villa area in Lichterfelde.

Things for my father always became worse. He had water in his legs and was constantly cold, so he would sit with his legs at the oven. In the last days he always stayed in bed, with stertorous breathing.[23] A nurse constantly stayed with him and helped him. In the morning of the 13th of April, 1929 he went to sleep. He had become 88 years old. Those who came to his funeral were Irene’s father, Uncle Gustav and his sister; Tante Elise with Hilde, her oldest daughter; Uncle Gustav, the brother of my mother from Breslau; Tante Trudel and Grandmother, many acquaintances, as well as neighbors.

When we arrived at the cemetery, my mother was horrified: the cemetery gardener had prepared the grave site that Grandfather wanted to be buried in, wherein his first wife had already been laid. In the other grave sites were the great-grand parents, Kleint. It was a good thing that Grandfather was not at the cemetery, because he was not doing well. My father was in the Warrior Association, so a band played, “I had a Comrade” at the grave (Ich hatte einen Komeraden). A few days later my father’s grave was exchanged. After the coffee [reception] Uncle Gustav drove home with Tante Elise; my mother’s brother stayed for a few more days; he slept at the house of his grandparents, whom he had seldom visited.

In September I was again at home and right away helped in the garden: plums had to be picked. I climbed up the tree and threw them to my mother in her basket. Tante Trudel also stood down there. Then Grandmother came into the garden with a man: it was Arthur Schlüter. He said that he had come to us twice and asked the neighbors about us, so he learned that we were with our grandparents. He invited me to a pastry shop. He had business in Berlin, so he wanted to visit me there some time. Now, however, he asked me if I would like to become his wife. I was so perplexed, I only shook my shoulders. For my sake he had come to Paulshof so often; I always thought he came to see Gottfried. “You surely have a friend; so I don’t want to step in between you.” He said as we separated and he again drove home. I felt that I was still too young to marry. His mother was dead and his married sister did the housekeeping; his brother-in-law helped him, so he probably really needed a diligent wife. Tante Trudel said, “Hanna, I would have taken that one. He made such a good impression, an owner of an estate in East Prussia.”

Grandfather read in the newspapers, that a representative was sought after in Seppau. “Write [and apply],” he said. So I wrote [and applied] there and sent along my papers.

On Sunday, right while I was coming out of the church, Ludwig stood outside and said, “You have to telephone Seppau immediately. Before I went to the post office to make the call, I first went home and hesitated. Finally I did go to the post office and made the call. “Come on Tuesday. You will be picked up from the railway station Little Tschirne,”[24] said the director. I first had to take a deep breath.

Seppau

In Seppau I learned that over thirty people had applied. They had sought out the oldest and the youngest and whoever called first that one would be taken. I had called up five minutes before [another], even though I had really dallied. The other one cried on the telephone; she had to support her mother and she was unemployed.

Seppau belonged to Count Schlabrendorf and Seppau. He had four propertied estates (Güter): Seppau, Great Kauer, which was situated in the next village. Tschepplau,[25] which was leased, but the huge forest was managed by a head-forester and Eleven;[26] and Lankau, which was managed by an inspector. The old count lived in the castle of Seppau. He was a smallish man with a stately countess from Sevelgo. They got to know each other in the theater and their oldest son was Count Alfred. Because his estates were indebted, the old count had a major trustee from Neumannbosel, who communicated with him only in writing. For short intervals he came into Joachim’s office, in which I also had my desk. The major dictated a letter to me which I had to deliver to the castle and give to the old count. He ranted and railed and dictated his answer to me, which I brought to the major and in that way it always continued. One time the count [was so] filled with rage he threw himself onto the carpet and looked at me. I rang for the old servant, who was a fine man. He lifted him up. He didn’t throw himself down in front of me again.

At the side of the castle stood two houses for the squires. The director lived in one of them. Attached to it was the quarters of the Monsieur, the old servant, the servant girl and the assistant. Then came the archway, on one side of which, lived the night watchman.

On one side of the office there was a long shelf that was full of files. In the evenings, I stood before them and read the labels.[27] The writing of the officials had still been sown into them. That was my job on Saturday afternoons. The Seppau assistant came one evening and said, “I’ll help you, so that you will soon find out how to do this.” Was I ever glad! In Great Kauer, the assistant was Mende, who only came to eat and only with the director and we too ate with him. Mrs. Joachim was a quiet, nice woman. For the second breakfast, she always brought me a mug of warm milk, because I looked so pale. She had a 19 year old son and a ten year old daughter. The assistants kept the book-accounts of the workers’ wages and the livestock reports. I did the bookkeeping for the natural reports and the large main account book. From Joachim and from Lanhau and Tschepplau, I received the weekly cash reports, all of which I recorded in the main account book.

Next to the office I had my room which was heated together with the office, in which stood an iron furnace that Mrs. Künze heated up in the mornings and also tidied up the office.

Every fourteen days I had to get up at 4:00 O’clock in the morning to go into the cow stalls and record the amount of milk given by each cow. Afterwards I stank frightfully and immediately had to change my clothes. Then a 6:00am I sat at my desk.

It was October and so the sugar beats had been taken out and put into a large farm wagon and driven to the railroad station in Little Tschirne and sent to the sugar factory. They always drove past my window and the road was not paved and so slime covered the whole street. I could only go outside with high laced shoes.

One afternoon the young count came into the office to inquire about something. I was not allowed to tell him anything, so I only shrugged my shoulders. “You dumb goose, “ he said, “why did you even come here?” and left. The father and son had become enemies. After a month the director said, “I am giving the secretary another fourteen days of vacation, so you can still stay until then.” So I stayed there until 12/1/1929. “Never again will I [work] in the country.” I told my mother. “I’ve had enough of that muck!” In the weekly newspaper someone had already asked for me, so I was immediately re-employed.

In July the company Ratsch was looking for office help, so I went to Mr. Fröhn, who was the Ratsch representative and introduced myself and received the position. [That made it possible] for me to often get together with Lotte Ehricht again. In the winter we often went to social entertainment and masked balls together. It is there that I met Rudi Steinchen. He was studying surveying in Berlin. He still knew classmates from Grünberg and they often met. Together with Lotte we did bicycle tours and went swimming in the Oder and on Sunday afternoons we often went dancing in a café.

After three quarters of a year a message arrived from Seppau asking me if I wanted to come back, because the secretary was leaving permanently. I took a deep breath. My mother said, “What they have saved for you, you should not turn down.” So I drove back.

But now some things had changed. I had to take over receiving all the mail from Seppau and for it received 20DM more per month. Therefore 70DM for food[28] and expenses and lodging, so I could send my mother 30DM a month, which [amounted to] the interest and payments for the house. I did not have to go into the cow stall in the mornings anymore, only distribute the payments in kind for the milk. An auditor came around every 14 days.

Siegfried Joachim invited his school comrades to his birthday [party] and he also invited me. There someone greeted me with the words: “We know each other, of course; we sat together in the same class.” But I could not remember him. From the post office in Gergau an official called me on the telephone and asked, “Are you Miss Behrens from Moschin? My name is Koch and I am the son of the country farm where you always picked up your milk.” He was married and had two children and invited me on a Sunday. He told me that his parents had remained there, but had been able to harvest little, because so much was stolen. Siegfried often drove to parties in Omaritz, which was the place where we also purchased all our groceries. One time I drove along with him to a party and there was good food to eat, good drinks, and also dancing; and because it got so late, I only allowed myself this entertainment that one time.

The director only remained one more year; he wanted to move to Breslau with his family, where he had several houses, which I heard from the workers. He came really poor and now left rich. For that the grain dealers and livestock handlers had helped him.

Now a man, Mr. von Sochow came to introduce himself. He had been recommended by the Princess Carolath and they both knew each other from their military times. At the same time Mrs. von Echenbrecher came with Ulla. The Joachims were looking for a house daughter. While Ulla was upstairs with Mrs. Joachim, Mrs. von Echenbrecher came to me in the office and questioned me about the children. I said, “The little Ilse is quite spoiled and Siegfried likes to play hooky from school. He was always late riding his bicycle to the train.” The children would see him coming from the window, while he only saw the rear lights of the leaving train. Mrs. Joachim is a nice woman, just somewhat sickly.

After Abendbrot I often played evening songs on the piano and sang them as well, above all Mr. Joachim liked love[29] songs and listened and smoked a cigar while sitting on the sofa. Outside he hollered a lot, which he probably had to do.

Eschenbrechers and Mr. von Sochow together were driven to the train. – When the Joachims were away, their whole apartment upstairs was renovated. I received a room in the castle, but I always had to go over to my office. We ate with the countess and her son. Mr. Mende from Great Kauer always ate earlier in the store. He thought that in the castle he would never be filled. The countess allowed herself to be given very little of the soup, hors d’oeuvres, main dish, and desert (twice) by the servant; she said, however, “Give everyone else a goodly portion.” I smirked at Mende, because at the end [of the meal he was too full] and could not eat anymore. For 14 days he no longer went to the inn to eat beforehand.

I had become friends with the daughter of the innkeeper and I accompanied her in the singing club to Schönau. Now the Sochows moved in and brought Ulla along. On the trip to the railway station Mr. von Sochow asked, if she was going to the Joachims; she said, “no,” so he expressed the opinion that she should come to them; he had two little daughters. Ulla was five years younger than me. For me the Sochows yearly received one pig, weekly 1 lb. of butter and also milk. I never paid attention to that, so I only learned about that later. The assistants received the same. I was really treated in a friendly manner by all. The girls, Annerose and Rottraut, soon became attached to me. Miss Bumusler, who for Mrs. v. Sochow had earlier been their tutor also came along. When Hans-Ewald was born, she slept with him above my room. One night she walked around a lot, so I asked her the next day, why she had been so restless. “I fed the little mouse,” she answered, “so it would not crawl into the Hans-Ewald’s little bed.” Now I had enough, and I immediately set a mouse trap in my room, but never was there a mouse in it.

The meals were not so luxuriant as with the Joachims, but to me it always tasted good. After butchering there were always more robust meals. Ulla told me that a great deal of sausages were made that Mrs. v. Sochow sent away. At Joachims he came to me in the office with tongue meat. We ate it together and had a drink of Schnapps. In the winter I was invited by the Forester, the gardener, millwright, shepherd and coachman for the butchering of the pigs, and I always let them give me fried blood sausage. The others ate curd meat,[30] which was too fatty for me. Later there was still coffee and cake, so it always got late. The women knitted and the men told stories and in that way I learned a lot about earlier times.

The count died in 1932. The countess had me come to the castle on Sundays to write addresses on envelopes. Count Wilhelm, the second son, who was an engineer in Munich, also dictated addresses to me. Among them were many of the high nobility, so I learned how to write addresses for the nobility.

Before the count went to the crematorium, he was left in state in the vestibule, where the family, all the employees, and servanthood took leave of him with a brief devotion. Elizabeth, the daughter, cried a few tears, but was immediately stopped by a poke by the countess. Elizabeth was a librarian in Berlin. Her engagement did not work out and the furniture, which had already been purchased stood in the house of the squire on the left of the castle. The youngest son was learning agriculture on another estate. On the next day I sat next to the coachman and we were driving to the railway station to pick up funeral guests. Four coaches followed behind us. I bade the funeral guests to climb into the coaches and [those] from the vicinity came with their automobiles. In the crematorium, where there were already several caskets, the burial took place. That was in a little forest opposite my office.

Count Alfred inherited everything, because it was entailed in the estate that it could not be divided.[31] He had to pay off his siblings [for their portion]. The Major dictated a letter to me for him, that he was the heir, etc. I had to write all his forenames, I believe there were ten and I had to include them all. Now the major no longer came to us in the office, but drove right to the castle. But now I had to be more with them instead of being [at the office]; I had to explain so much to the count and also write [notifying] all the officials. He had a larger typewriter that I preferred to type on. Saturday at 11:00am he always called me on the telephone. He then told Mrs. v. Sochow that I would eat with him. The countess, to whom I always brought her mail at noon, was very friendly to me. One time on a Sunday afternoon I played the piano in the castle. A glorious grand piano was there. The door opened and suddenly the countess appeared. “Oh, it’s you,” she said. “Feel free to continue playing.” The Sochows had only a harmonium (a reed organ) which I played at the house.

Ewald’s baptism took place in the upper floor of the Sochows and when the pastor addressed the sponsors, saying, “Answer with yes.” Little Rottraut answered in a really loud voice, “Yes.” She was only four years old. We were all amused. Often I sang an evening song to both girls, when they could not go to sleep. Mrs. v. Sochow always asked me [for this help], because she could not sing. My father sang for each birthday child in the morning at their bedside, “Because I am Jesus’ little Sheep,” before he congratulated us.

On one day, Rottraut did not want to eat, because it did not taste good to her. Mrs. v. Sochow said, “Go to Miss Hanna.” She brought her plate with her, took a place beside me. I fed her and she ate it all up. Later both of them went to school in Schönau. Annerose was as delicate as her mother, so she was sent to school one year later. Daily at 10:00 I had to take all the items to the post office. Riding my bicycle on the avenue, I took both girls along on the bike, then set them down on the street where they then ran to the school in Schönau. On Sunday mornings they often came to my bed and I had to tell them stories. We would have breakfast at 9 O’clock. When they came home from school they first greeted me in my office. On Sundays I often went for a walk with Ulla and the children. Sadly Ulla was only with us for one year. She got a rash on her hands from primrose, which did not go away, so she drove home. But even until today I have remained connected with her. Every evening she came into my room; we smoked a women’s cigarette together, which her mother sent to us. Ulla also fell in love with Mende, who always went around properly dressed in riding pants and boots, was tall and slender and had black hair and eyes. He always had to come and eat from Great Kauer and always came earlier to have a conversation with me in the office. Mr. v. Sochow had left already earlier, into the inn to drink a Schnapps, as Frieda Walter told me. At the end of the month a larger bill had probably been run up together and that put the married couple into a dismal mood. Once in a while I was also invited, where I was always offered a cigarette and at 10:00 he always opened the window, and that meant, time to go to sleep.

Mrs. v. Sochow asked me if I did not know of anybody to replace Ulla. I thought of Anne Weyer, who had my position, so I wrote to her, and she then came right away. Sadly she was petulant like at home,[32] so after a quarter of a year she was laid off. Mrs. von Sochow talked with me beforehand. And I felt sorry about this let-down. Anne was ashamed to drive back home and asked me if she could drive to my house and [live there a while]. I told her, that Wally had a child and there was little room [for here there].

Lotte Ehricht came one Sunday to Seppau and told me that Wally had given birth to Heinz. I was shocked and angry that they had lied to me. When I was home the last time, I asked why Wally had become so fat. Upon that my mother said, “She gets pills from the physician, which make her fat.” and I believed her. Anne, who was jealous that I so often wrote to Rudi and also celebrated holidays with him in Schönau, went to Mrs. Steinchen, who lived in Grünberg one street away from where we lived, and told her about Wally, and that I was amusing myself in Seppau. She thought that Wally should have gone into the water[33] and wrote to Rudi, that he should give up on me.

For a long time I did not receive any mail and then [Rudi] wrote me that he was uncertain that he would pass his exam and he did not want to let me wait so long. I was very unhappy. Some letters were still shared back and forth and then the friendship was over. The Sochows certainly noticed how aggrieved I was, so Father,[34] who was, of course, the teacher of Annerose and Rottraut, often invited me, so we got to know each other.

I saw Rudi only one more time, as I came home on a Sunday evening with a large suitcase. Wally had gotten me from the railroad station and he stood there on the street. He came to us and wanted to take and hold the suitcase for us. I thanked him and left his standing there. My mother soon sent Anne Weyer back home; she had never written. If she had married Arthur Schlüter, even then she would not have been a good girlfriend.

After a year I told the count that the work had become too much for me. So he told me, “Then we will provide another office help for you.” I knew that Else Feller, a friend of Lotte Ehricht, was unemployed and I wrote to her and she came immediately, but stayed only one year. She did not like the work schedule. The count would first appear at 9:00, at 14:00 there was lunch (Mittagbrot), then [Else] could probably loaf, but that meant that she had to sit longer in the evening. He only dictated letters to her for the typewriter, which she had to finish, make carbon copies of them and then file them. We were together for some hours, did needlework together, and Sundays we often took walks.

Then Hilde Hirsch came from Glogau. She told me that the count had recently been with her and asked her, if she was also as good as I. I would do everything by myself. I had a good relationship with her. In the evenings she often came to me and taught me table tennis. On the one side of my office stood a long and low table, which had two extensions. We moved it into the hall and played. It did not take long and I was able to beat her. Father and Günther Franz, who was the home school teacher at the Jordans, sometimes came over on a Sunday afternoon and watched. It was too bad that Hilde Hirsch also only stayed for a year. Her friend was angry that she had left from Glogau. She then worked at a newspaper in Glogau. Every month, of course, I had to go to the Darmstädter Bank to get money for Schilter and Sons, so I visited Hilde Hirsch, if I still had more time. After Walsdorf, she wrote me, that she had given birth to a son.

Now the count again put out an advertisement, to which Else Feller responded. He did not want to hire her again and asked me to provide someone again. I knew that the Parson in Dalkau was looking for a woman teacher and he had several addresses. So I rode my bicycle to see him and let him give me some of the [names]. One name was Frederieke from Schweinfurt. We visited each other. Later she made up her diploma (Abitur) and became the teacher. We took a secretary, Agathe, from Berlin. She came from a good house and was not modest. She did not at all like the work with the count and stayed only a half a year. Then a Miss Hetzke answered the advertisement. She was one year younger than I, related with a married dentist, who often visited her in the evenings. I had not befriended her, but mornings she often came to me in the office, the castle was too lonely a place for her. She could not have stayed long, because when the war began, the count telephoned the post office in Walsdorf,[35] that I should come to the telephone.